Basic graphics¶

Introduction¶

The path module allows one to construct PostScript-like paths, which are one of the main building blocks for the generation of drawings. A PostScript path is an arbitrary shape consisting of straight lines, arc segments and cubic Bézier curves. Such a path does not have to be connected but may also comprise several disconnected segments, which will be called subpaths in the following.

Todo

example for paths and subpaths (figure)

Usually, a path is constructed by passing a list of the path primitives

moveto, lineto, curveto, etc., to the constructor of

the path class. The following code snippet, for instance, defines a

path p that consists of a straight line from the point \((0, 0)\) to the

point \((1, 1)\)

from pyx import *

p = path.path(path.moveto(0, 0), path.lineto(1, 1))

Equivalently, one can also use the predefined path subclass

line and write

p = path.line(0, 0, 1, 1)

While already some geometrical operations can be performed with this path (see

next section), another PyX object is needed in order to actually being able to

draw the path, namely an instance of the canvas class. By convention,

we use the name c for this instance:

c = canvas.canvas()

In order to draw the path on the canvas, we use the stroke() method of the

canvas class, i.e.,

c.stroke(p)

c.writeEPSfile("line")

To complete the example, we have added a writeEPSfile() call, which writes

the contents of the canvas to the file line.eps. Note that an extension

.eps is added automatically, if not already present in the given

filename. Similarly, if you want to generate a PDF or SVG file instead, use

c.writePDFfile("line")

or

c.writeSVGfile(“line”)

As a second example, let us define a path which consists of more than one subpath:

cross = path.path(path.moveto(0, 0), path.rlineto(1, 1),

path.moveto(1, 0), path.rlineto(-1, 1))

The first subpath is again a straight line from \((0, 0)\) to \((1,

1)\), with the only difference that we now have used the rlineto class,

whose arguments count relative from the last point in the path. The second

moveto instance opens a new subpath starting at the point \((1,

0)\) and ending at \((0, 1)\). Note that although both lines intersect at the

point \((1/2, 1/2)\), they count as disconnected subpaths. The general rule

is that each occurrence of a moveto instance opens a new subpath. This

means that if one wants to draw a rectangle, one should not use

rect1 = path.path(path.moveto(0, 0), path.lineto(0, 1),

path.moveto(0, 1), path.lineto(1, 1),

path.moveto(1, 1), path.lineto(1, 0),

path.moveto(1, 0), path.lineto(0, 0))

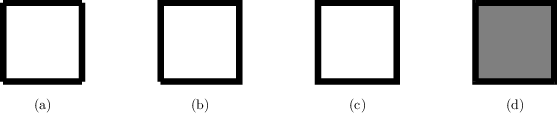

which would construct a rectangle out of four disconnected subpaths (see Fig. Rectangle example a). In a better solution (see Fig. Rectangle example b), the pen is not lifted between the first and the last point:

Rectangle example¶

Rectangle consisting of (a) four separate lines, (b) one open path, and (c) one closed path. (d) Filling a path always closes it automatically.

rect2 = path.path(path.moveto(0, 0), path.lineto(0, 1),

path.lineto(1, 1), path.lineto(1, 0),

path.lineto(0, 0))

However, as one can see in the lower left corner of Fig. Rectangle example b,

the rectangle is still incomplete. It needs to be closed, which can be done

explicitly by using for the last straight line of the rectangle (from the point

\((0, 1)\) back to the origin at \((0, 0)\)) the closepath

directive:

rect3 = path.path(path.moveto(0, 0), path.lineto(0, 1),

path.lineto(1, 1), path.lineto(1, 0),

path.closepath())

The closepath directive adds a straight line from the current point to

the first point of the current subpath and furthermore closes the sub path,

i.e., it joins the beginning and the end of the line segment. This results in

the intended rectangle shown in Fig. Rectangle example c. Note that filling the

path implicitly closes every open subpath, as is shown for a single subpath in

Fig. Rectangle example d), which results from

c.stroke(rect2, [deco.filled([color.grey(0.5)])])

Here, we supply as second argument of the stroke() method a list which in

the present case only consists of a single element, namely the so called

decorator deco.filled. As its name says, this decorator specifies that

the path is not only being stroked but also filled with the given color. More

information about decorators, styles and other attributes which can be passed as

elements of the list can be found in Sect. Attributes: Styles and Decorations. More

details on the available path elements can be found in Sect.

Path elements.

To conclude this section, we should not forget to mention that rectangles are, of course, predefined in PyX, so above we could have as well written

rect2 = path.rect(0, 0, 1, 1)

Here, the first two arguments specify the origin of the rectangle while the second two arguments define its width and height, respectively. For more details on the predefined paths, we refer the reader to Sect. Predefined paths.

Path operations¶

Often, one wants to perform geometrical operations with a path before placing it on a canvas by stroking or filling it. For instance, one might want to intersect one path with another one, split the paths at the intersection points, and then join the segments together in a new way. PyX supports such tasks by means of a number of path methods, which we will introduce in the following.

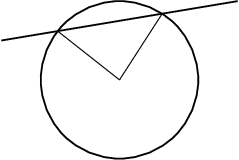

Suppose you want to draw the radii to the intersection points of a circle with a straight line. This task can be done using the following code which results in Fig. Example: Intersection of circle with line yielding two radii

from pyx import *

c = canvas.canvas()

circle = path.circle(0, 0, 2)

line = path.line(-3, 1, 3, 2)

c.stroke(circle, [style.linewidth.Thick])

c.stroke(line, [style.linewidth.Thick])

isects_circle, isects_line = circle.intersect(line)

for isect in isects_circle:

isectx, isecty = circle.at(isect)

c.stroke(path.line(0, 0, isectx, isecty))

c.writePDFfile()

Example: Intersection of circle with line yielding two radii¶

Here, the basic elements, a circle around the point \((0, 0)\) with radius

\(2\) and a straight line, are defined. Then, passing the line, to the

intersect() method of circle, we obtain a tuple of parameter values of

the intersection points. The first element of the tuple is a list of parameter

values for the path whose intersect() method has been called, the second

element is the corresponding list for the path passed as argument to this

method. In the present example, we only need one list of parameter values,

namely isects_circle. Using the at() path method to obtain the point

corresponding to the parameter value, we draw the radii for the different

intersection points.

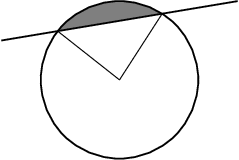

Another powerful feature of PyX is its ability to split paths at a given set of parameters. For instance, in order to fill in the previous example the segment of the circle delimited by the straight line (cf. Fig. Example: Intersection of circle with line yielding radii and circle segment), one first has to construct a path corresponding to the outline of this segment. The following code snippet yields this segment

arc1, arc2 = circle.split(isects_circle)

if arc1.arclen() < arc2.arclen():

arc = arc1

else:

arc = arc2

isects_line.sort()

line1, line2, line3 = line.split(isects_line)

segment = line2 << arc

Example: Intersection of circle with line yielding radii and circle segment¶

Here, we first split the circle using the split() method passing the list

of parameters obtained above. Since the circle is closed, this yields two arc

segments. We then use the arclen(), which returns the arc length of the

path, to find the shorter of the two arcs. Before splitting the line, we have to

take into account that the split() method only accepts a sorted list of

parameters. Finally, we join the straight line and the arc segment. For this, we

make use of the << operator, which not only adds the paths (which could be

done using line2 + arc), but also joins the last subpath of line2 and the

first one of arc. Thus, segment consists of only a single subpath and

filling works as expected.

An important issue when operating on paths is the parametrisation used. Internally, PyX uses a parametrisation which uses an interval of length \(1\) for each path element of a path. For instance, for a simple straight line, the possible parameter values range from \(0\) to \(1\), corresponding to the first and last point, respectively, of the line. Appending another straight line, would extend this range to a maximal value of \(2\).

However, the situation becomes more complicated if more complex objects like a

circle are involved. Then, one could be tempted to assume that again the

parameter value ranges from \(0\) to \(1\), because the predefined

circle consists just of one arc together with a closepath

element. However, this is not the case: the actual range is much larger. The

reason for this behaviour lies in the internal path handling of PyX: Before

performing any non-trivial geometrical operation on a path, it will

automatically be converted into an instance of the normpath class (see

also Sect. path.normpath). These so generated paths are already separated

in their subpaths and only contain straight lines and Bézier curve segments.

XXX explain normpathparams and things like p.begin(), p.end()-1,

A more geometrical way of accessing a point on the path is to use the arc length of the path segment from the first point of the path to the given point. Thus, all PyX path methods that accept a parameter value also allow the user to pass an arc length. For instance,

from math import pi

r = 2

pt1 = path.circle(0, 0, r).at(r*pi)

pt2 = path.circle(0, 0, r).at(r*3*pi/2)

c.stroke(path.path(path.moveto(*pt1), path.lineto(*pt2)))

will draw a straight line from a point at angle \(180\) degrees (in radians \(\pi\)) to another point at angle \(270\) degrees (in radians \(3\pi/2\)) on a circle with radius \(r=2\). Note however, that the mapping from an arc length to a point is in general discontinuous at the beginning and the end of a subpath, and thus PyX does not guarantee any particular result for this boundary case.

More information on the available path methods can be found in Sect. Class path — PostScript-like paths.

Attributes: Styles and Decorations¶

Attributes define properties of a given object when it is being used. Typically, there are different kinds of attributes which are usually orthogonal to each other, while for one type of attribute, several choices are possible. An example is the stroking of a path. There, linewidth and linestyle are different kind of attributes. The linewidth might be thin, normal, thick, etc., and the linestyle might be solid, dashed etc.

Attributes always occur in lists passed as an optional keyword argument to a method or a function. Usually, attributes are the first keyword argument, so one can just pass the list without specifying the keyword. Again, for the path example, a typical call looks like

c.stroke(path, [style.linewidth.Thick, style.linestyle.dashed])

Here, we also encounter another feature of PyX’s attribute system. For many

attributes useful default values are stored as member variables of the actual

attribute. For instance, style.linewidth.Thick is equivalent to

style.linewidth(0.04, type="w", unit="cm"), that is \(0.04\) width cm

(see Sect. Module unit for more information about PyX’s unit system).

Another important feature of PyX attributes is what is call attributed merging. A trivial example is the following:

# the following two lines are equivalent

c.stroke(path, [style.linewidth.Thick, style.linewidth.thin])

c.stroke(path, [style.linewidth.thin])

Here, the style.linewidth.thin attribute overrides the preceding

style.linewidth.Thick declaration. This is especially important in more

complex cases where PyX defines default attributes for a certain operation. When

calling the corresponding methods with an attribute list, this list is appended

to the list of defaults. This way, the user can easily override certain

defaults, while leaving the other default values intact. In addition, every

attribute kind defines a special clear attribute, which allows to selectively

delete a default value. For path stroking this looks like

# the following two lines are equivalent

c.stroke(path, [style.linewidth.Thick, style.linewidth.clear])

c.stroke(path)

The clear attribute is also provided by the base classes of the various styles.

For instance, style.strokestyle.clear clears all strokestyle subclasses

i.e. style.linewidth and style.linestyle. Since all

attributes derive from attr.attr, you can remove all defaults using

attr.clear. An overview over the most important attribute types provided by

PyX is given in the following table.

Attribute category |

description |

examples |

|---|---|---|

|

decorator specifying the way the path is drawn |

|

|

style used for path stroking |

|

|

style used for path filling |

|

|

type of path filling |

|

operations changing the shape of the path |

||

|

attributes used for typesetting |

|

transformations applied when drawing object |

|

Todo

specify which classes in the table are in fact instances

Note that operations usually allow for certain attribute categories only. For example when stroking a path, text attributes are not allowed, while stroke attributes and decorators are. Some attributes might belong to several attribute categories like colours, which are both, stroke and fill attributes.

Last, we discuss another important feature of PyX’s attribute system. In order

to allow the easy customisation of predefined attributes, it is possible to

create a modified attribute by calling of an attribute instance, thereby

specifying new parameters. A typical example is to modify the way a path is

stroked or filled by constructing appropriate deco.stroked or

deco.filled instances. For instance, the code

c.stroke(path, [deco.filled([color.rgb.green])])

draws a path filled in green with a black outline. Here, deco.filled is

already an instance which is modified to fill with the given color. Note that

an equivalent version would be

c.draw(path, [deco.stroked, deco.filled([color.rgb.green])])

In particular, you can see that deco.stroked is already an attribute

instance, since otherwise you were not allowed to pass it as a parameter to the

draw method. Another example where the modification of a decorator is useful

are arrows. For instance, the following code draws an arrow head with a more

acute angle (compared to the default value of \(45\) degrees):

c.stroke(path, [deco.earrow(angle=30)])

Todo

changeable attributes